The fundamental nature of international conflict is undergoing a profound transformation. The concept of hybrid warfare sought to capture this change by challenging the way we think about, and plan for, a rapidly mutating threat landscape.[1] Though innovative in many respects, the hybrid warfare paradigm has still only somewhat tangentially incorporated cyber warfare into models of contemporary organized armed violence, such as the influential construct known as New War.[2]

New War is said to consist of both regular and irregular warfare that is financed in novel ways and waged by a new, decentralized array of conflict actors, who harbor new motives and employ new tactics. Despite increasingly common references to the cyber dimension in hybrid warfare thinking, however, too little attention has been paid to the changing nature of the cybersecurity field’s fundamental threat categories (actors, their skills and resources, as well as their motives, threat vectors, etc.). It is time to renew our commitment to gaining a better understanding of the conflict/threat environment we occupy. This can be done by looking at cybersecurity’s contribution to our understanding of hybrid warfare through the lens of the New War model. The resulting way of thinking might be termed New-Hybrid Warfare.

From New War to New-Hybrid Warfare

According to Mary Kaldor’s celebrated New War paradigm, contemporary organized armed violence differs from that of earlier eras in several important respects. New War takes place in the context of globalization’s unprecedented level of economic, political, social, and digital interconnectedness. Modern conflict is now waged by a complex, decentralized, array of actors, the lines among which are increasingly blurred. These include state and non-state actors, from national armed forces to paramilitary and mercenary groups, down to civilian militias and even criminal gangs. New War actors often employ “weapons of the weak,” including the terroristic targeting of civilians to control areas that are often uncontrollable by military force alone. Many New War efforts are not state financed but are instead funded by criminal enterprises that help create, as well as exploit, the chaos of New War.[3]

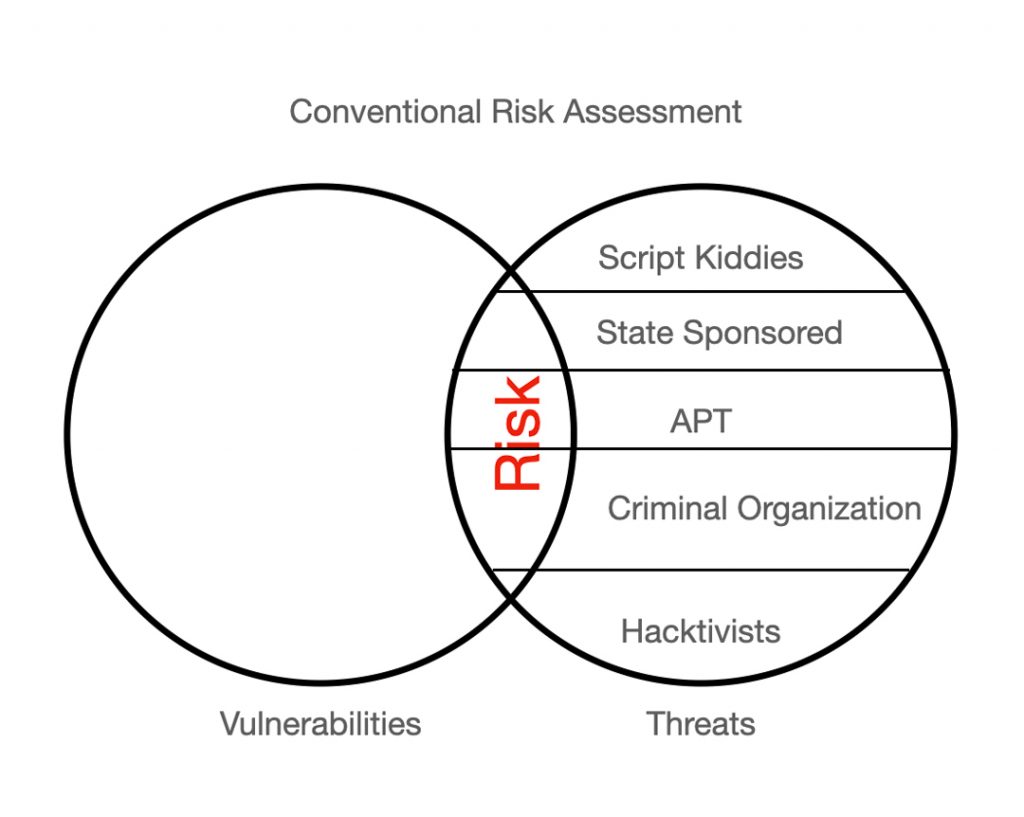

Despite a span of 15 years since Frank Hoffman announced the era of hybrid warfare[4], too little has changed in the structure of the basic cybersecurity frameworks of threats, threat actors, and threat vectors. For example, despite considerable evidence to the contrary, state sponsored agents, criminal elements, and political hacktivists are all still commonly thought to constitute wholly discrete, mutually exclusive categories. Failing to see, however, the ways in which lines among these types of actors are increasingly blurred undermines our capacity for more finely tuned risk assessment. As the myriad linkages among established and emerging threats seem to indicate, trying to maintain firm distinctions among putative state-sponsored actors, criminal syndicates, politically motivated hacktivists, and in some cases even nationalism-inspired script kiddies and misinformation campaigners, is rather quixotic.

Revelations from the takedown of The Hive suggest that it is but the most recent confirmatory case.[5] Though known to be Russian-speaking and widely believed to have connections to Russian state entities,[6] the ransomware group is often referred to as a merely criminal organization.[7] This is despite the fact that its members also have a fairly transparent nationalist, geopolitical agenda in tune with a political hacktivist program. And though one is cautioned against concluding that the group enjoys official Russian state sponsorship, it would be foolish to discount that strong probability. Indeed, all this reveals the Hive, much like its even more infamous cousin Sandworm, to be far more than merely “some profit-focused bank-fraud racket.”[8] Yet, while both have assiduously targeted Ukraine, Moscow’s most coveted prize, they remain identified essentially by their criminal motives.[9]

Force Multiplication and Risk

It is important to recognize that researchers such as Bruce Schneier have long cautioned against over-hyping the threat of cyber warfare,[10] and others conclude “that cyber attacks are not (yet) effective as tools of coercion in war.”[11] Articulating a New-Hybrid Warfare paradigm, however, is not necessarily a call to recognize a categorically heightened threat matrix. But it is at least about the challenges for risk assessment posed by a more complex threat landscape. In the context of New War, the blending of regular and irregular forces has increased the capacity of actors to pursue military objectives beyond what the scope of their limited resources would predict. The same is true in the realm of new-hybrid warfare.

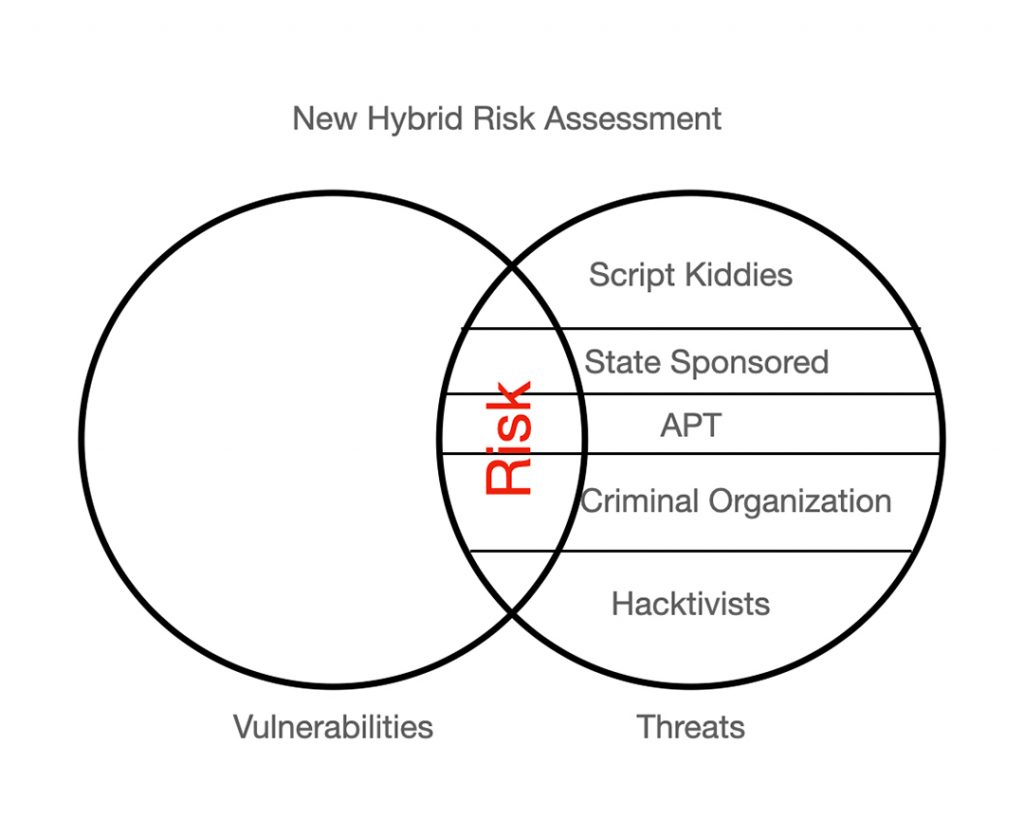

The Hive’s criminal objectives have been served not only by deployment of its ransomware, but by offering it as Ransomware-as-a-Service (RAAS). This has important ripple effects throughout the threat landscape. Of equal if not greater significance than the Hive’s expanded earnings gained from the affiliate RAAS model is the fact that its illicit marketing effectively upgrades the sophistication and capacity of actors who would otherwise be incapable of autonomously scripting at such a level. Hive ransomware deployed by modestly skilled “script kiddies” can have impacts normally associated with far more advanced script writers. Landing in the hands of actual script writers with significant skills of their own can lead to outcomes normally associated with only the world’s most elite hackers.

Figures 1 and 2 below show the implications of these dynamics for the level and composition of risk. The risk in Figure 2, the area of overlap between vulnerabilities and threats, is slightly greater but considerably more complex than that in Figure 1. The availability of ransomware to well-resourced but perhaps poorly skilled hackers generates the modest increase in risk as well as the greater diversity of threat actors who significantly contribute to that risk (i.e., the change in the degree to which script kiddies, for example, contribute to risk).

It’s Cyber, but is it War?

It is widely held that the distinction between hybrid war and “actual” war is still a meaningful one. That is to say, the view that “hybrid warfare means to wage war below the threshold of actual warfighting”[12] is still one with considerable purchase. Unfortunately, this conception of war, in which cyber-attacks play an important role only prior to, or at an intensity below, armed violence, is an antiquated one. It fails to account for the myriad ways cyber-attacks against public, private and commercial targets might not only lay the groundwork for subsequent military assaults, but are, in fact, adjuncts to the use of armed violence against an adversary throughout all phases of a conflict. It is not likely that those in a war zone suffering winter without heating care one whit whether the payload that knocked out their grid was delivered by rockets or by malware.

In fact, the impact on civilians wrought by cyber-attacks might be one of the best indicators that cyber warfare is an integral dimension of contemporary “real” war. The International Committee of the Red Cross, custodians of International Humanitarian Law (IHL), or the laws of war, holds that, “IHL limits cyber operations during armed conflicts just as it limits the use of any other weapon, means and methods of warfare in an armed conflict, whether new or old.”[13] Were that not the case, says cyber warfare and IHL expert Tilman Rodenhäuser, we would face “an absurd situation” in which IHL would prohibit attacking a hospital with a missile, but would do nothing to prohibit taking down that same hospital’s life-saving medical devices, computers, and networks simply because the former attack was kinetic and the latter cyber.[14]

Conclusion

The old ways of war are receding into history. What stands in their stead is very much a work in progress, but we can begin to sketch the broad contours of New-Hybrid Warfare. For a start, the cyber dimension of New-Hybrid Warfare is not a pre-war, or sub-war condition. The distinction between kinetic and cyber weapons is an important one, but it does not imply a simple hierarchy of significance. Large-scale kinetic weapons can and do wreak physical destruction on such staggering scales that they begin to take on an indiscriminate quality. This seems to indicate a uniqueness to kinetic weapons. Perhaps that might be true for their physicality, but it is less true with respect to how indiscriminate many cyber weapons are. Indeed, many cyberweapons are inherently indiscriminate, which puts them at odds with the laws of war in the same way as kinetic weapons when deployed indiscriminately.

Those who wage modern conflict are a complex amalgam of actors separated by increasingly fuzzy boundaries, and this is true in both the cyber and kinetic dimensions of modern conflict. Whether it be mercenary soldiers deployed alongside combatants wearing the uniform of the nation-state, or whether it be agents of a state’s security agency launching cyber-attacks against a foe that is simultaneously being targeted by nationalism-inspired hacktivists, state and non-state actors are increasingly indistinguishable.

These are the complex conditions that constitute New-Hybrid Warfare. ![]()

[1] “Conflict in the 21st Century: The Rise of Hybrid Wars,” Frank G. Hoffman, 2007.

[2] New & Old Wars: Organized Violence in a Global Era, Mary Kaldor, 2012.

[3] “In defence of new wars,” Mary Kaldor, 2012

[4] “Conflict in the 21st Century: The Rise of Hybrid Wars,” Frank G. Hoffman, 2007.

[5] U.S. Department of Justice Disrupts Hive Ransomware Variant,” United States Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs, 26 January, 2023.

[6] “Uncle Sam slaps $10m bounty on Hive while Russia ban-hammers FBI, CIA,” Jessica Lyons Hardcastle, 27 January 2023.

[7] “What Makes the Hive Ransomware Gang That Hacked Costa Rica So Dangerous?” Sumeet Wadhwani, 18 November 2022

[8] Sandworm: A New Era of Cyberwar and the Hunt for the Kremlin’s Most Dangerous Hackers, Andy Greenberg, 2019.

[9] “Sandworm gang launches Monster ransomware attacks on Ukraine,” Jeff Burt, 29 November 2022.

[10] “The Threat of Cyberwar Has Been Grossly Exaggerated,” Schneier on Security, 7 July, 2007.

[11] “Invisible Digital Front: Can Cyber Attacks Shape Battlefield Events?,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Nadia Kostyuk and Yuri M. Zhukov, 10 November 2017.

[12] Nielen, Anders Puck, ”What is Hybrid Warfare?”

[13] “International Humanitarian Law and Cyber Operations during Armed Conflicts,” ICRC Position Paper, November 2019.

[14] “Cyber Warfare: does International Humanitarian Law apply?” International Committee of the Red Cross, 25 February 2021.

Brett R. O’Bannon, PhD

Leave a Comment